Мережі у Крипто VC

Як засновник, знання про те, які VC часто спінвестують, може заощадити вам час і вдосконалити вашу стратегію залучення коштів. Кожна транзакція - це відбиток пальця. Ми могли б розгорнути історії, які вони розповідають, коли ми візуалізуємо їх на графіку.Як клас активів, венчурний капітал діє в умовах екстремальних законів влади. Але ступінь, в якій це відбувається, не вивчена, оскільки ми постійно доганяємо останню наративу. Протягом останніх кількох тижнів ми створили внутрішній інструмент, який відстежує мережі всіх криптовалютних венчурних капіталістів. Але чому?

Основний увігляд простий. Як засновник, знання того, які VC часто співінвестують, може заощадити вам час і покращити вашу стратегію залучення коштів. Кожна транзакція - це відбиток пальців. Ми могли б розгорнути історії, які вони розповідають, якщо б ми їх візуалізували на графіку.

Іншими словами, ми могли б відстежувати вузли, відповідальні за більшість залучених капіталів у криптосфері. Ми намагалися знайти порти в сучасній торговій мережі, схожі на купців тисячоліття тому.

Є дві причини, чому ми вважали, що це буде цікавий експеримент.

Ми керуємо мережею венчурів, яка діє трохи як Fight Club. Ніхто не кидає ударів (покищо), але ми також не дуже про це говоримо. Мережа венчурів включає приблизно 80 фондів. У всьому Крипто VC, приблизно 240 фондів витратили понад 500 тис. доларів на стадії засіву. Це означає, що ми безпосередньо зв'язані з ⅓ з них, і майже ⅔ читають наш вміст. Це рівень охоплення, якого я не очікував, але ось ми.

Проте часто важко відстежити, хто саме розгортається де. Відправка звітів засновнику кожному фонду стає шумом. Трекер виник як фільтруючий інструмент для розуміння, які фонди розгорнулися, в яких секторах і поруч з ким.

Для засновників важливо знати, куди було спрямовано капітал, - це лише перший крок. Ціннішою є розуміння того, як фонди виконуються, і з ким вони зазвичай спільно інвестують. Щоб це зрозуміти, ми розрахували ймовірність того, що інвестиція фонду отримає наступне фінансування, хоча на пізніших етапах (наприклад, Серія В), де компанії часто випускають токени замість традиційного збору капіталу, це стає неоднозначним.

Допомога засновникам визначити, які інвестори активні в криптовалютному VC, була першим кроком. Наступним було розуміння того, які джерела капіталу фактично працюють краще. І коли у нас були ці дані, ми могли дослідити, які фонди спільно інвестують для досягнення кращих результатів. Звичайно, це не ракетна наука. Ніхто не може гарантувати раунд серії A тільки тому, що хтось виставив чек. Точно так само, як ніхто не може гарантувати шлюб після першого побачення. Але це дійсно допомагає знати, в що ви втягуєтеся, як на побаченнях, так і в підйомах венчурів.

Архітектура успіху

Ми використовували базову логіку, щоб визначити фонди, які отримують найбільше наступних раундів у своєму портфелі. Якщо після стартового раунду фонд бачить, що кілька фірм залучають капітал, це, ймовірно, означає, що він робить щось правильно. VC бачать, що вартість їх інвестицій зростає, коли фірма залучає капітал за вищою оцінкою в наступному раунді. Таким чином, наступні раунди слугують як достойна міра продуктивності.

Ми взяли 20 фондів з найбільшою кількістю наступників у своєму портфелі, потім розрахували загальну кількість фірм, в які вони інвестували на початкових етапах. Ви можете ефективно розрахувати ймовірність того, що засновник збереже наступника з цього показника. Якщо фірма зробила 100 перевірок на початковому етапі і 30 з них побачили наступника за два роки, ми розраховуємо ймовірність закінчення на рівні 30%.

Тут важливо дотримуватися жорсткого фільтру у два роки. Дуже часто стартапи можуть вирішити зовсім не збирати гроші. Або збирати їх після цього періоду.

Степеневі закони є екстремальними навіть серед топ-20 фондів. Наприклад, підвищення від A16z означає, що у вас є 1 шанс на 3 здійснити ще одне підвищення через два роки. Це означає, що для кожних трьох стартапів, що підтримує A16z, один піде на підвищення серії A. Це досить високий рівень випуску, враховуючи, що інший кінець цього спектра - це шанс 1 з 16.

Венчурні фонди, які займають ближче до 20 місця (у цьому списку з 20 найкращих фондів з послідовними операціями), мають 7% ймовірність того, що фірма піде на іншу збірку коштів. Ці цифри виглядають схоже, але для контексту 1 шанс з 3, як кинути число менше трьох на кидку кубика. 1 з 14 - приблизно ймовірність народження близнюків. Це дуже різні результати. Буквально і ймовірнісно.

Жарти поза сторону, що це показує - це ступінь агрегації в межах криптовенчурних фондів. Деякі венчурні фонди можуть розробити наступний раунд зборів для власної портфельної компанії, оскільки вони також мають фонд зростання. Таким чином, вони б розгортались на початковому етапі та серії А в тій же фірмі. Коли венчурний фонд подвоюється володінням більше однієї компанії, це зазвичай надсилає здоровий сигнал інвесторам, які приєднуються в пізніших раундах. Іншими словами, наявність фонду зростання в межах VC-фірми значно впливає на ймовірність успіху фірми в наступні роки.

Довгий хвіст цього полягатиме в тому, що венчурні фонди в крипто розвиватимуться для проведення приватного еквіті для проєктів, які мають значні обсяги доходів.

У нас був теоретичний аргумент на користь цього переходу. Але що насправді показують дані? Щоб вивчити це, ми врахували кількість стартапів у нашому інвестиційному кохорті, які отримали наступні інвестиції. Потім ми розрахували відсоток фірм, де той самий венчурний фонд знову взяв участь у наступному раунді.

Тобто, якщо фірма залучила засів від A16z, яка ймовірність того, що A16z розгорне капітал у їхній серії A?

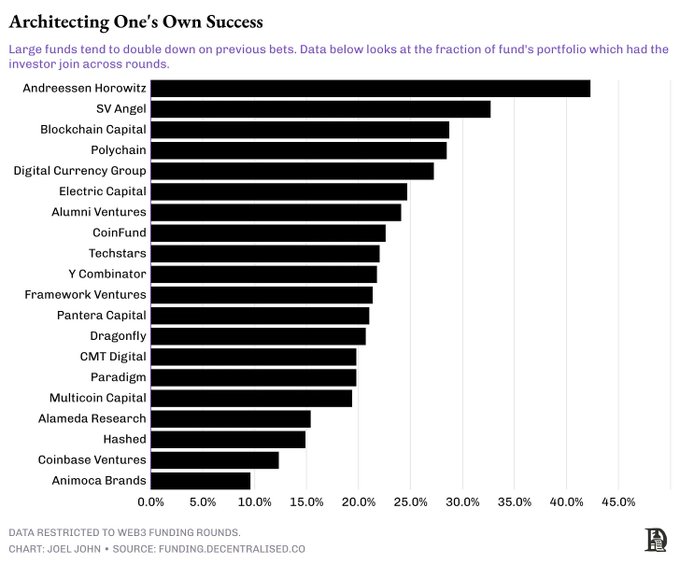

Шаблон стає досить очевидним досить швидко. Великі фонди, що опрацьовують північ від мільярда, віддають перевагу частим наслідуванням. Наприклад, 44% усіх стартапів, які перейшли до збору додаткових коштів в портфелі A16z, побачили участь A16z у наступному раунді. Blockchain Capital, DCG та Polychain виписують чеки для чверті своїх інвестицій, що бачать інший збір.

Іншими словами, від кого ви піднімаєтеся на насінній або передсіяльній стадіях має значення набагато більше, ніж ви могли б уявити, просто тому, що ці інвестори часто віддають перевагу підтримці своїх власних фірм.

Звичайно співінвестувати

Ці шаблони є функцією минулого. Ми не маємо на увазі, що фірми, які збирають кошти від VC, відмінні від найкращих, приречені на провал. Метою всіх економічних зусиль є або зростання, або створення прибутку. Венчурні проекти, які вдаються здійснити будь-яку з цих функцій, з часом будуть цінуватися вище. Але це, безумовно, допомагає підвищити ймовірність успіху. Один зі способів підвищити свої шанси, якщо ви не здатні залучити кошти з цієї групи (з перших 20), - пройти через їхню мережу. Іншими словами, зв'язки з цими центрами для залучення капіталу.

Зображення нижче розглядає мережу всіх венчурних інвесторів у криптосистемі протягом останнього десятиліття. Є 1000 інвесторів, які діляться ~22 тис. з'єднаннями між собою. Якщо індивідуальний інвестор спільно інвестує з іншим, утворюється зв'язок. Воно може виглядати переповненим або навіть здаватися, що вибір величезний.

Проте це стосується коштів, які померли, ніколи не повертали гроші або більше не розгорталися.

Шумно, я знаю.

Реальність того, куди ми рухаємося як ринок, стає зрозумілішою на зображенні нижче. Якщо ви засновник, який хоче залучити серію А, пул коштів, які інвестували в раунди на суму понад 2 мільйони доларів, становить близько 50. Мережа інвесторів, які долучилися до такого раунду, налічує близько 112 фондів. І ці фонди все більше консолідуються, демонструючи сильніші переваги для спільного інвестування з конкретними партнерами.

Море інвесторів, з яких ви можете залучити кошти на Seed до серії A

Здається, що кошти мають тенденцію формувати звички спільних інвестицій з часом. Тобто фонд, який інвестує в одну сутність, має тенденцію приєднувати поруч з собою фонд-рівня за його доповнюючими навичками (наприклад, технічними, або допомагає з GTM) або на основі партнерських відносин. Для вивчення того, як працюють ці відносини, ми почали досліджувати патерни спільних інвестицій між фондами за останній рік.

Наприклад, за останній рік,

Polychain та Nomad Capital діляться 9 спільними інвестиціями.

Bankless має 9 спільних інвестицій з Robot Ventures.

Binance та Polychain мають 7 спільних інвестицій.

Акції Binance мають стільки ж спільних інвестицій з HackVC.

Так само, OKX та Animoca мають 7 спільних інвестицій.

Великі фонди все більше вибагливі стосовно своїх спінвесторів.

Минулого року, наприклад, з 10 ставок, зроблених Paradigm, Robot Ventures приєднався до трьох раундів.

DragonFly поділився трема раундами з Robot Ventures та Founders Fund в загальній кількості здійснених ними 13 інвестицій.

Так само, Founders Fund мав загалом три спільних інвестиції з Dragonfly в загалом 9 зроблених ними ставок.

Іншими словами, ми переходимо до часу, коли кілька фондів роблять більші ставки, з меншою кількістю спінвесторів. І багато з цих спінвесторів, як правило, є встановленими, добре відомими іменами, які існують вже довгий час.

Увійдіть у Матрицю

Інший спосіб вивчення даних - це аналіз поведінки найактивніших інвесторів. Матриця вище враховує фонди з найбільшою кількістю інвестицій з 2020 року та те, як відбувається взаємозв'язок між ними. Ви помітите, що акселератори (такі як Y Combinator або Outlier Venture) мають декілька спільних інвестицій з біржами (такими як Coinbase Ventures).

З іншого боку, ви також зрозумієте, що обмінники регулярно мають свої власні вподобання. OKX Ventures, наприклад, має велику кількість спільних інвестицій з Animoca Brands. Coinbase Ventures має понад 30 інвестицій з Polychain та ще 24 з Pantera.

Що ми бачимо, це структурно три речі.

Акселератори, як правило, мають кілька спільних інвестицій з біржами або більшими фондами, незважаючи на високу частоту інвестування. Це, ймовірно, пов'язано з вподобаннями етапу.

Великі біржі, як правило, мають великі уподобання до венчурних фондів на етапі зростання. Наразі Пантера та Полічейн домінують у цьому аспекті рівняння.

Біржі зазвичай грають з місцевими гравцями в геополітичних справах. Як OKX Ventures, так і Coinbase показують відмінні вподобання стосовно того, з ким вони співінвестуватимуть. Це просто підкреслює глобальний характер розподілу капіталу в межах Web3 сьогодні.

Таким чином, якщо венчурні фонди агрегуються, звідки береться наступна частина маржинального капіталу? Цікавий патерн, який я помітив, полягає в тому, що корпоративний капітал має власні кластери. Наприклад, Goldman Sachs має 2 спільних раунди з PayPal Ventures та Kraken за весь час свого існування. Coinbase Ventures зробила 37 спільних інвестицій з Polychain, 32 з Pantera та 24 з Electric Capital.

На відміну від венчурного капіталу, корпоративні фонди зазвичай орієнтовані на стартапи на етапі зростання з важливим PMF. Тому залишається побачити, як себе поводитиме цей фонд капіталу в умовах, коли фінансування стартапів на ранніх етапах зменшується.

Еволюція мереж

З “Квадрат і Вежа”

Я вирушив бажаючи працювати над мережею відносин у криптосвіті після прочитанняКвадрат і вежа Найл Фергюсонадекілька років тому. Це розкриває, як поширення ідей, продуктів, а навіть хвороб може бути пов'язане з мережами. Це стало очевидним лише до того, як ми побудували інформаційну панель фінансування кілька тижнів тому, що я усвідомив, що візуалізація мережі зв'язків між джерелами капіталу в криптосистемі навіть можлива.

Я вважаю, що такі набори даних і природа економічних взаємодій між цими сутностями можуть бути використані для розробки (і виконання) М&As та викупу токенів від приватних сутностей. Обидва з цих аспектів ми досліджуємо внутрішньо. Їх також можна використовувати для BD та ініціатив у сфері партнерства. Ми все ще виробляємо способи зробити набір даних доступним вибраним фірмам.

Але вернімося до теми.

Чи дійсно мережі допомагають фонду виходити вперед?

Відповідь трохи складна.

Здатність фонду вибирати правильну команду та надавати капітал у великому розмірі матиме значення все більше, ніж його доступ до інших фондів. Однак важливою буде індивідуальна взаємодія Генерального Партнера (ГП) з іншими співінвесторами. VC не діляться потоком угод за логотипами. Вони діляться ним з людьми. І коли партнер змінює фонди, зв'язок просто переноситься на їх новий фонд.

Я мав відчуття з цього, але мав обмежені можливості перевірити аргумент. На щастя, у 2024 році булодокумент, який вивчавяк вели себе топ-100 VC з часом. Насправді, вони вивчили 38 000 раундів в загальній складності 11084 компаній і навіть розкладали це на сезонність ринків. Суть їхньої аргументації полягає в декількох фактах.

Минулі спільні інвестиції не означають майбутньої співпраці. Фонд може вирішити не співпрацювати з іншим фондом, якщо попередні ставки виявилися невдалими.

Спільні інвестиції зазвичай зростають під час періодів манії, оскільки фонди намагаються активніше розгортати свої кошти. VC більше покладаються на соціальний сигнал і менше на документальну перевірку під час періодів манії. Під час спадного ринку фонди розгортаються обережно і часто самостійно через менші оцінки.

Кошти обирають партнерів на підставі доповнюючих навичок. Так оточення інвесторів, які спеціалізуються на одному й тому ж, зазвичай є причиною проблем.

І, як я вже казав, в кінцевому підсумку, спільні інвестиції не відбуваються на рівні фонду, а на рівні партнера. У моїй власній кар'єрі я бачив, як люди переходять з однієї організації в іншу. Мета часто полягає в тому, щоб працювати з тією ж самою людиною, незалежно від того, до якого фонду вони приєднуються. У вікові штучного інтелекту, який бере на себе роботу людини, важливо знати, що людські взаємини все ще є основою діяльності венчурного капіталу на ранніх стадіях.

Є багато роботи, яка залишається в цьому дослідженні того, як формуються крипто-VC мережі. Наприклад, я б з радістю вивчив вподобання ліквідних хедж-фондів у розподілі капіталу. Або як пізній етап розгортання в криптовалюті змінився з часом у відповідь на сезонність ринку. Або як M&A та приватний капітал входять в гру. Відповіді знаходяться десь у даних, які маємо сьогодні, але знадобиться час, щоб сформулювати правильні питання.

Так само, як і багато інших речей у житті, це буде тривале дослідження, і ми обов'язково будемо виводити сигнал, якщо знайдемо його.

Disclaimer:

- Ця стаття роздрукована з [ Децентралізовано.Co]. Усі авторські права належать оригінальному авторові [@shloked_ та @joel_john95]. Якщо є заперечення щодо цього перевидання, будь ласка, зв'яжіться з Gate Learnкоманда, і вони оперативно цим займуться.

- Відповідальність за відмови: Погляди та думки, висловлені в цій статті, є виключно тими, що належать автору та не становлять жодних інвестиційних порад.

- Команда Gate Learn робить переклади статей на інші мови. Копіювання, поширення або плагіат перекладених статей заборонені, якщо не зазначено інше.

Пов’язані статті

Що таке Coti? Все, що вам потрібно знати про COTI

Все, що вам потрібно знати про Blockchain

Що таке Стейблкойн?

Що таке Gate Pay?

Що таке BNB?